Women Warriors of Japan – The Role of the Arms-Bearing Women in Japanese History by Ellis Amdur

Introduction

The entry of Asian martial arts into the Western world has happened to coincide, through no particular design, with the transformation of women’s role in society. Women of the late twentieth century have risen into prominence in business, science, and as players on the political stage. The victimization of women in domestic violence and sexual and physical assault is still rampant, but it is increasingly countered through legislation and political activism and, on a personal level, through women’s pursuit of fighting skills to defend themselves. Ever greater numbers of women are involved in martial arts and self-defence training.

For most people, identifying with one’s predecessors is a strong desire. One often models oneself on an ideal that is personified in heroic myths or tales. For many women interested in Japanese martial practice, there is the image of the woman warrior bearing a naginata in the protection of her home and even on the field of battle. Although it is a glorious image, it is difficult to separate fact from fancy because of the almost complete absence of historical records that document the role of arms-bearing women.

Early History

The battle tales of Japan, chronicles of wars in the Heian, Kamakura, and Muromachi periods, focus almost completely on the deeds of the nobility and warrior classes. These tales, passed down by blind bards much as Homer’s Iliad, present warriors as archetypes: the tragic Loser-Hero, the Warrior-Courtier, the Traitor, the Coward, etc. Women warriors are almost never described or even mentioned.

Women’s roles in such tales are slight: the Tragic Heroine who kills herself at the death of her husband; the Loyal Wife who is taken captive; the Stalwart Mother who grooms her son to take vengeance for his father’s death; the Merciful Woman whose “weak” and “feminine” qualities encourage a warrior chieftain to indulge in unmanly empathy and dissuade him from slaughtering his enemy’s children, who later grow up to kill him; and the Seductress who preoccupies the warrior leader and diverts him from his task with her feminine wiles. Finally, almost casually mentioned, are women en masse: either slaughtered or “given” to the warriors as “spoils-of-war.” That they were surely raped and often murdered was apparently considered too trivial a fact to even mention in later warrior tales once the conventions of the genre had been codified, just as the wholesale burning and pillaging of peasants’ farms was considered such a matter of course that it ceased to be mentioned, as if such repeated references would only disturb the flow of narrative. Unless one is willing to imagine a conspiracy of silence in which women’s role on the battlefield was suppressed in both historical records and battle-tales, it is a fair assumption that onna-musha (women warriors) were very unusual. This is borne out, I believe, by the prominence given to the few women about whom accounts are written. The most famous women warriors are Tomoe Gozen and Hangaku Gozen (sometimes called Itagaki). Interestingly, for both of these women the naginata was not their weapon of choice.

Tomoe Gozen from Kuniyoshi’s “One Hundred Heroes” story

In the Heike Monogatari, Tomoe Gozen appears as a general in the troops of Kiso Yoshinaka, Yoritomo’s first attack force. She was described as follows:

Tomoe was especially beautiful, with white skin, long hair, and charming features. She was also a remarkably strong archer, and as a swords-woman she was a warrior worth a thousand, ready to confront a demon or a god, mounted or on foot. She handled unbroken horses with superb skill; she rode unscathed down perilous descents. Whenever a battle was imminent, Yoshinaka sent her out as his first captain, equipped with strong armor, an oversized sword, and a mighty bow; and she performed more deeds of valor than any of his other warriors.

—Tale of the Heike1

Her last act, on the verge of Yoshinaka’s defeat, is the subject of many plays and poems. To buy time for her husband to commit seppuku, she rode into the enemy forces and, flinging herself on their strongest warrior, unhorsed, pinned, and decapitated him. In the interim, however, Yoshinaka was killed by an arrow. There are legends that she was killed, and others that she survived to become a Buddhist nun. There is also a legend that she was taken captive by Wada Yoshimori and had a son, Asahina, considered to be the strongest warrior of the later Kamakura era.

However, Tomoe has not ever been proven to be an historical figure–and this was not for lack of trying. She has exerted a fascination upon the Japanese for hundreds of years in the startling image of a beauteous woman who was also a breaker of wild horses and the equal of any man. Tomoe is claimed by more than a few naginata traditions to be either their founder or one of their primordial teachers. There is, however, no historical justification for such claims. She lived centuries before their martial traditions were even dreamed of.

The second famous woman warrior is Hangaku Gozen, daughter of the Jo, a warrior family of Echigo province. She was known for her strength and accuracy with the bow and arrow. In 1201, after the feudal government attempted to subjugate one of her nephews, the warriors of Echigo and Shinano revolted. Besieged in Tossaka castle, she held off the enemy from the roof of a storehouse. After being wounded in both legs by spears and arrows, she was taken prisoner and presented before the Shogun Yoriie. Drawn by her beauty and dignity, Yoshito Asari of the Kai Genji courted her and they married. The stories do not say if this union was coerced or a match of equals. According to one account, they lived the rest of their lives in peace, but in another account, she was killed while assisting in the defence of Torizakayama Castle.

Thus, at least in the earlier periods such as the Heian and Kamakura, women who became prominent or even present on the field of battle were the exception rather than the rule. This does not indicate, however, that most women were powerless. There is a common image of Japanese femininity based on the accounts we have of women of the Imperial Court, swaddled in layers of kimono and rigid custom, preoccupied with poetry and moon viewing. But such a picture obscures just who the bushi women were during the ascendancy of their class. They were originally pioneers, helping to settle new lands and, if need be, fighting, like women of the old western territories in American history. Some bushi clans may even have been led by women. This can be inferred from the legal right given to women to function as jito (stewards), who supervised land held in absentia by nobles or temples.

Muhen-ryu naginata

Bushi women were trained mainly with the naginata because of its versatility against all manner of enemies and weapons. It was generally the responsibility of women to protect their homes rather than go off to battle, so it was important that they become skilled in a few weapons that offered the best range of techniques to defend against marauders who often attacked on horseback. Therefore, it makes sense that women were sometimes adept with the bow due to its effectiveness at long-range and often with the naginata as it was an effective weapon against horse riders at closer range. In addition, most women are weakest at close quarters where men can bring their greater weight and strength to bear. A strong, lithe woman armed with a naginata could keep all but the best warriors at a distance, where the advantages of strength, weight, or sword counted for less.

The Warring States Period

Detail from “A Night Attack on the Horikawa” by Yoshitora

From the tenth century on, Japan can never be said to have been at peace. But in 1467, the whole country was swept into chaos in what became known as the Sengoku Jidai (Warring States Period, circa 1467 c.e. through 1568 c.e.). It was a time in which all social classes were swept up into war. Feudal domains were sometimes stripped of almost all healthy men, who hired themselves out as nobushi (mercenaries), were drafted into armies, or slaughtered in battle. As a result of this rampant warfare, women were often the last defence of towns and castles.

In this period there are accounts of the wives of warlords, dressed in flamboyant armour, leading bands of women armed with naginata. In an account in the Bichi Hyoranki, for example, the wife of Mimura Kotoku, appalled by the mass suicide of the surviving women and children in her husband’s besieged castle, armed herself and led eighty-three soldiers against the enemy, “whirling her naginata like a waterwheel.” She challenged a mounted general, Ura Hyobu, but he refused, claiming that women were unfit as opponents to true warriors. He edged backwards in cowardice, saying under his breath, “She is a demon!” She refused to back down, but while his soldiers attacked her, he escaped. She cut through her attackers and won her way back to the castle.

It was probably at this time that the image of women fighters with naginata arose. However, as Yazawa Isao, a sixteenth-generation headmistress of Toda-ha Buko-ryu wrote (in 1916), the main weapon of most women in these horrible times was not the naginata, but the kaiken, which Bushi women carried at all times. Yazawa stated that a woman was not usually expected to fight with her dagger. Instead, she was required to kill herself in a manner as wrapped in custom as the male warrior’s seppuku. This was known as jigai. In seppuku, a man was required to show his stoicism in the face of unimaginable pain by disemboweling himself. In jigai, women had a method in which death would occur relatively quickly. The nature of the wound was not likely to cause an ugly distortion of the features or disarrangement of the limbs that would offend the woman’s dignity after death. The dagger was used to cut the jugular vein.

Women did not train in using the kaiken with sophisticated combat techniques. If a woman was forced to fight, she was to grab the hilt with both hands, plant the butt firmly against her stomach, and run forward to stab the enemy with all her weight behind the blade. She was to become, for a moment, a living spear. She was not supposed to boldly draw her blade and challenge her enemy. She had to find some way to catch him unawares. If she were successful in this, she would most likely be unstoppable. More often than not, however, a woman could not expect to face a single foe nor, even then, to have the advantage of surprise. If she were captured alive, even after killing several enemies, she would be raped, displayed as a captive, or otherwise dishonoured. In the rigid beliefs of this period, women would thereby allow shame to attach to their name. The only escape from what was believed to be disgrace was death at one’s own hands.

The Edo Period: An Enforced Peace

In the mid-seventeenth century, when Japan finally arrived at an enforced peace under the authoritarian rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, the need for skill at arms decreased. The turbulent energies of the warrior class were restrained by an intricate code of conduct based upon laws governing behaviour appropriate to each level of society. The rough codes of earlier warriors were codified into the doctrines of bushido–the “way of the warrior.” Self-sacrifice, honour, and loyalty became fixed ideals, focusing the energies of the warrior class on a new role as governing bureaucrats and police agents in a society under an enforced, totalitarian peace. The role of the warrior was mythologized, and certain images held up as ideals for all to emulate. That these doctrines were primarily a Confucian political ideology rather than a way for active warriors to survive is shown by the fact that the original reference to these codes was “shido” (in Chinese, the way of the “gentleman”), a direct reference to Confucian concepts.

Everyone was required to fill an immutable role in society, fixed at birth and held until death. The rules and social conventions governing conduct between men and women, formerly somewhat more egalitarian, became more rigid than in any other period of Japanese history. A woman’s relationship towards her husband was said to mirror that of a samurai towards his lord. The bushi woman was expected to centre her life around her home, serving her family in the person of her husband first, his sons second, and her mother-in-law third. Studies and strong physical activity were considered unseemly. Work was almost completely gender divided, and the lives of men and women became increasingly separate from one another. There was usually a room in each house reserved for men which women were forbidden to enter, even to clean or serve food. Husbands and wives did not even customarily sleep together. The husband would visit his wife to initiate any sexual activity and afterwards would retire to his own room.

The stories of women warriors defending their homes and their families became means to define a woman’s role in society. They trained with the naginata less to prepare for combat than to instil them with the idealized virtues necessary to be a samurai wife. A women’s work was unremitting service to the males of the household and tireless effort to teach proper behaviour to her children, who were legally considered to be her husband’s alone. However, unlike the upper-class women of Victorian England, who were expected to be subservient and frail, the bushi women were expected to be subservient and strong. Their duty was to endure.

When a bushi woman married, one of the possessions that she took to her husband’s home was a naginata. Like the daisho (long and short swords) that her husband bore, the naginata was considered an emblem of her role in society. Practice with the naginata was a means of merging with a spirit of self-sacrifice, of connecting with the hallowed ideals of the warrior class. As men were expected to sacrifice themselves for the state and the maintenance of society, women were expected to sacrifice themselves to a rigid, limited life in the home.2 No longer carried on the battlefield,3 the use of the naginata was confined to practice with wooden replicas in the many martial traditions.

In the mostly peaceful years of the Edo period, martial systems often fissioned, each faction specializing in one or another weapon. Many schools focusing on the use of the naginata were created and began to be increasingly associated with women.

In some villages, women maintained an active role in maintaining order. The mother of one of my instructors told how when she was a small girl in a village in Kyushu, the southernmost major island of Japan, men were often gone from the village in certain seasons to join up on labour crews. When there was a disturbance at night or a suspicious character entered the village, the women would grab their naginata, which hung ready on one of the walls of the house, and go running outside to gather and search the town for any danger. Her grandmother was the leader of this “emergency response squad,” and they were a naturally autonomous group within the village. Protecting the neighborhood was simply assumed to be one of their functions.

Tendo Ryu: One foot on the Battlefield, One in the Modern World

Tendo-ryu naginatajutsu exemplifies many of the most significant changes that occurred in martial training from the late sixteenth century to the present. These include:

- the transition from a warrior’s art incorporating many weapons to a martial tradition with a decided emphasis on a single one;

- the increasing perception of the naginata as a weapon associated with women;

- the transition of martial arts from combative training to a training of will and spirit;

- the use of martial arts training in mass education;

- the development of sportive forms of martial training.

The founder of Tendo-ryu is said to be Saito Denkibo Katsuhide. His original school, Ten-ryu was developed sometime in the 1560s, a time of chaos and warfare. Some traditions state that he studied with Tsukahara Bokuden, the founder of the famous Kashima Shinto-ryu. Legends of Ten-ryu assert that Saito went into retreat at a shrine in Kamakura. One night, in an incident curiously reminiscent of the Biblical tale of Jacob wrestling with the angel, he got into a fight with a mountain ascetic. After a battle lasting until dawn, Saito asked his opponent his school’s name. Saying nothing, the man walked away towards the sun. In a moment of inspiration, Saito realized the name to be Ten-ryu, “Heaven’s Tradition.”

This story is illustrative of the fact that an “enlightenment” experience does not necessarily endow an individual with any moral virtues. Saito remained a flamboyant, pugnacious man. In some accounts, he is described wearing a kimono in imitation of feathers as if he were a tengu (mountain goblin). After many duels, he killed his last opponent at the age thirty-eight. He was later ambushed by the dead man’s followers, who fired arrows from several directions. He was able to knock down many of the arrows with a kamayari (long-hafted sickle), but finally was killed, “as full of arrows as a hedgehog has quills” as one modern writer put it. Saito’s arrow-blocking method supposedly became the basis of some of the central techniques of Tendo-ryu naginatajutsu.

Ten-ryu had a rather violent history during the Edo period and quite a few of its members were involved in well-known duels with people from other schools (see Chapter 2 of ‘Old Schools’.

Like many of the ryu of that period, Ten-ryu included the study of a number of weapons–their kenjutsu, in particular, became renowned. The oldest records of the school include instructions for the study of sword and numerous other weapons, as well as battlefield tactics, fighting on horseback, hand-to-hand combat, and esoteric philosophical teachings. Over time, the ryu fissioned into a number of lines that specialized in sword, spear, or other weapons. Mitamura Kengyo, headmaster of one line in the late 1800s, singled out the naginata particularly for the training of women and girls. Mitamura’s line, at some point, began to refer to their tradition as Tendo-ryu, “The Tradition of the Way of Heaven.”

Group training in Tendo-ryu under the direction of Headmistress Mitamura Takeko

Mitamura helped organize the Seitokusha, a school of Shinto and martial arts practice in an effort to combat the steady influx of Western influence. In 1895, his group merged with the Dai Nippon Butokukai, a national regulating body of martial arts. After displaying his methods for group teaching in 1899, he was contracted by the large Doshisha women’s school in Kyoto to teach on a regular basis. Women took prominence as teachers (most notably, Mitamura’s brilliant wife, Mitamura Chiyo), and the practice weapon was made lighter.4

There are 120 two-person kata surviving, featuring the naginata, sword, kusarigama, jo (mid-length staff), two swords, and short sword. The person in the teaching position, called uketachi (receiving sword), is always armed with a sword. (From this point on, the uketachi will be referred to as the “instructor.”) The instructor’s function is to serve as “cooperative opposition,” thereby enabling the students to hone their skills.

Group training in Tendo-ryu under the direction of Headmistress Mitamura Takeko

The vast bulk of the forms feature the naginata as shitachi (users sword), which is the learner’s role. (From this point on, the shitachi will be referred to as the “practitioner”). It is unclear when these forms were developed, although it is quite unusual for older martial systems to contain so many forms emphasizing a single weapon such as the naginata. It is thus a fair surmise that more and more forms were probably added over time as practitioners attempted to add either their personal stamp or more sophistication to the curriculum of the school.

Group training in Tendo-ryu under the direction of Headmistress Mitamura Takeko

The techniques are first practiced singly and then, after a time, with a partner. Several decades ago, I observed the midsummer practice at the Shubukan Dojo near Osaka, where practitioners from all over Japan gather to train together. One of my enduring memories of this school was the sight of perhaps one hundred women, under the direction of current headmistress Mitamura Takeko, granddaughter of Mitamura Kengyo and Mitamura Chiyo, cutting and thrusting through their basic techniques in sweeping arcs of perfect unity.

The basic forms are a series of crisp, spiraling movements of the naginata against the sword. These naginata forms often utilize cuts to the wrist or underarm. Ichi monji no midare, the technique Saito Denkibo is said to have used to cut down arrows 400 years ago, forms the basis for many kata.

Although the roots of Tendo-ryu were developed during a time of war, many of the techniques of the original Ten-ryu have surely been abandoned or lost. In spite of this, the people who practice Tendo-ryu today have been able to maintain a large part of the spirit and frame of reference of those times. The kata are practiced to instill a sense of fighting awareness. Mitamura Takeko calls it the “cut and thrust spirit.” She believes that practicing in this way can help one to reach deep inside oneself. “I don’t just practice the naginata, it is a part of me.” She states that even though a student practices killing, “the gentleness and softness inherent in a woman is not lost. In fact, the training is aimed at focusing those traits into a strength which can be used for fostering and protecting as well as taking life.”

Tendo-ryu kusarigamajutsu

The instructor usually initiates the kata, maintaining a spacing perhaps one half step outside that which would be appropriate to strike the practitioner. Tendo-ryu found this necessary because otherwise the naginata wielder’s movements may become cramped and abbreviated as she tried to safely accommodate her cuts so as not to strike the instructor standing within range. Thus, Tendo-ryu’s forms are geared to the development of the naginata’s technique, allowing the practitioner to cut with full power and extension.

The instructor, while trying to draw and lead the practitioner, is by no means passive. The teachers constantly remind both sides to attack, not receive. There are two main kiai, (use of the voice and breath to create or foster certain feelings or reactions in oneself or one’s opponents), one for calling or pulling your opponent toward you (TOH!) and the deciding kiai. This final kiai is executed in two ways: a short forceful “EH!” to accompany and strengthen cuts and a piercing “spiraling” manner “Eeeehhh!” to enhance thrusts. Smoothness of breath and the maintenance of postural integrity while breathing deeply are emphasized.

Some of the kata, featuring both naginata and short sword, are very realistic about the limitations of the long weapon. Since the naginata is not very effective in close fighting, it is thrown aside as the swordfighter gets inside its arc. The short sword is quickly drawn and used to stab the swordfighter. This type of form harkens back to two sources: combat grappling, in which fighters would use small weapons on the belt, and the use of the dagger by women fighting an opponent who attempted to use his greater mass and skill at close combat to overwhelm her.

Some of the senior practitioners still train in the other weapons of the school. These include techniques with the chain-and-sickle, a five-foot staff that simulates the haft of a naginata with the blade broken off, and some very intriguing forms featuring two swords.

Perfect combat spacing between Headmistress Mitamura Takeko (right) and Sawada Hanae (left) of Tendo-ryu

Tendo-ryu’s main dojo is the Shubukan in Osaka, but there are powerful groups in many other areas of Japan. The members, almost all women, ranging from slender and young to stout and old, are not exceedingly formal. There is much laughter, affection, and love. But during the practice of the kata, there is a razor-sharp focus found in few dojos anywhere. Unlike some schools, which claim to have remained largely unchanged since their inception, it is likely that Tendo-ryu is far different than the original Ten-ryu practiced by the wild Saito Denkibo Katsuhide. Nonetheless, perhaps the best of his spirit still resides in the hands and hearts of the women of Tendo-ryu, a courage and integrity in movement anyone would do well to emulate.

Jikishin Kage Ryu Naginata-do and the Development of Meiji Budo

At roughly the same time that Mitamura Kengyo and other teachers were initiating a renaissance in Tendo-ryu, another remarkable school of naginata, the Jikishin Kage-ryu Naginata-do was born. This school claims its roots in Jikishin Kage-ryu sword technique, developed by the famous monk Ippusai out of older Shinkage-ryu sword schools. Ippusai’s ryu, one of the most significant of the Edo and Meiji periods, has deep connections with esoteric and mystical teachings and was one of the first schools to engage in competitive practice with split bamboo swords.

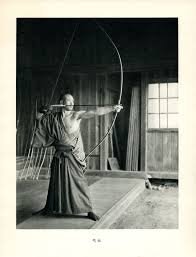

Toya Akiko, Headmistress of the Jikishin Kage-ryu, using the naginata

In the 1860s, Satake Yoshinori, a student of the Jikishin and Yanagi Kage-ryu, developed a new naginata school with his wife, Satake Shigeo. She had studied martial arts since she was six years old and was famous for her strength with the naginata. Together they developed the forms of present day Jikishin Kage-ryu naginata-do. An innovative work, it bears no discernible relation to Ippusai’s Jikishin Kage-ryu ken-jutsu. The addition of the suffix “do,” (way) indicates that the founders saw their school as a budo, a means of martial practice for the purpose of self-perfection rather than self-preservation.

Headmistress Toya Akiko with kusarigama

The succeeding head teacher, Sonobe Hideo, took Jikishin Kage-ryu into girls’ schools. She taught at major schools in the Kyoto area and was one of the first teachers to popularize mass training. The system has continued to grow and has the most students of any of the traditional schools of naginata. The present head teacher is Toya Akiko.

The forms of Jikishin Kage-ryu are done in straight lines in a highly defined rhythm. The kiai is traded back and forth, in almost a call-and-response, adding to a sense of dance-like structure. The forms project a aura of crisp elegance.

Training in Jikishin Kage-ryu naginata

The emphasis appears to be on correct performance rather than development of martial skills. When a mistake was made in the practices that I observed, the kata was discontinued and started over. Even senior teachers seemed unable to respond spontaneously to unexpected movements by their partners. Thus, it seems to me that perfection of the form rather than an ability to improvise freely is the aim of the school.

Training in Jikishin Kage-ryu naginata

Their naginata is a very light, relatively short weapon, held in a rather narrow grip at one end of the haft and whirled around a central axis. The curve of the blade is not used to deflect attacks of the sword, and the cuts and thrusts are straight. Almost all the forms are oriented towards practice for the naginata, with the sword merely receiving attacks. There are also a few collateral forms featuring a highly stylized practice of the chain-and-sickle against the sword. The spacing between the partners is such that it is unlikely that the sword would be able to strike a damaging blow in most circumstances.

Training in Jikishin Kage-ryu naginata

Despite its seemingly non-combative orientation, Jiki-shin Kage-ryu first made its name in matches against kendo practitioners. Both Satake Shigeo and Sonobe Hideo became famous by their many victories in such contests. These days, Jiki-shin Kage-ryu no longer emphasizes competition against kendo practitioners, although they do still occur. Many members do participate in competitions in the modern, sports-oriented atarashii naginata (see below).

Training in Jikishin Kage-ryu kusarigama

Jikishin Kage-ryu is clearly a valued part of its practitioner’s lives. Their main dojo seems to be a place of joyous health and good spirits, full of both laughter and serious, finely honed practice. This seems in keeping with Jikishin Kage-ryu’s intention to create a system that will attract large numbers of women from many differing lifestyles. Jikishin Kage-ryu has been more successful than any other martial system of the last one hundred years in appealing to a large population of Japanese women. In the forms of this system, they find a kind of semi-martial training that encourages the development of a strong, yet graceful femininity.

The Birth of Modern Competitive Martial Sports

The Jikishin Kage-ryu exemplifies a universalistic trend that grew in the Meiji period (1868-1912 c.e.). The late Meiji era was the first time the Japanese thought of themselves as having a national identity. Before the Meiji period, one’s feudal domain was, in many senses, one’s country.

Jikishin Kage-ryu naginata-do Headmistress Toya Akiko and Higashi Tomoka, a senior instructor

The government began to manipulate the doctrines of bushido to make them apply to the entire populace rather than just the warrior class. Through this, the government encouraged the development of a regimented and obedient society. Language, religion, and education were brought under centralized control. The dogma of the day elevated the Emperor to the status of a god. Shinto was also perverted into a state religion, professing a pseudo-history that was used as a rationale for the “manifest destiny” of Japan as the ruler of Asia. Following the same pattern of activities as the European and American imperialist powers, these sentiments carried the country through a war with Russia, the rape of northern China, and the horrors of World War II. Loyalty to the Emperor replaced loyalty to a daimyo (clan leader).

Used as a rallying point, this loyalty created an entire nation that was willing to live and die in the service of any cause deemed worthy by the government. The newly created grammar school system became a great propaganda machine. The primary emphases were on submission to the Emperor and gaining skills and knowledge for the good of the state. Students were taught that cooperation, standardization, and the denial of personal desires were the most productive ways of serving the nation.

Around 1910, martial arts practice was made a regular part of school curricula. The classical disciplines, however, were not considered completely suitable for the training of the mass population. The older martial traditions encouraged a feudalistic loyalty to themselves and their teachings and, in addition, often focused on somewhat mystical values not directly concerned with the assumed needs of modern Japan.

For this reason, judo and kendo, both Meiji creations, were taught in boys’ schools. Kendo had been standardized by teachers of some of the major traditional systems of sword fighting for the purpose of specializing in competitive training. The length and weight of the shinai (split bamboo replica sword) was fixed–rather longer than a real sword–and the protective clothing was standardized. The head, sides of the trunk, the wrists, and a thrust to the throat became acceptable targets. All other strikes and thrusts, no matter how potentially lethal did not count for points.

Kendo developed from competitive practices with protective equipment called uchiaigeikko (striking-together practice) developed in a number of different sword schools. This method became a relatively safe way to gauge each other’s skills when compared to the only other alternatives: a duel, using wooden or edged weapons or a rather abstract evaluation of an individual’s forms. Conservative martial artists, however, found this competitive style to be absurd. With such safety equipment and body armor, one could take all sorts of “risks,” diving in to strike while allowing the edge of the opponent’s “weapon” to slide across the femoral artery or the back of the neck with no thought to the fatal injury one would suffer were one dueling with real weapons. Without the fear of either losing one’s life or the dread of physical pain and injury, the conservatives felt that people moved unnaturally both in body and in spirit, becoming sportsmen rather than warriors. The innovative practitioners felt, on the other hand, that in the absence of warfare or other conflict, kata training had degenerated into a sterile repetition of forms. Such innovators saw more conservative types as simply repeating a dull round of stereotyped movements offering no means of testing the validity of their techniques, nor any insight into how they might perform with an opponent not “colluding” with them. As time passed, some ryu, such as the schools associated with Itto-ryu and Jikishin Kage-ryu became famous for their strong practice using protective equipment. Others, such as Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto-ryu, never attempted to integrate this method into their practice.

In the early Meiji period, there was another impetus for the development of competitive martial sports This was the phenomenon of roving martial “carnivals” known as gekken kogyo (gekken means “attacking sword”; kogyomeans “a show”). Some former samurai, down on their luck, joined forces in traveling exhibitions, giving demonstrations and taking challenges from the audiences. Mounting the stage, fighters would challenge all comers from the audience, using wooden or bamboo swords, naginata, spear, chain-and-sickle, or any other weapon selected by the challenger. These fights were very popular and well written up in the newspapers. Although the fighters probably tried to exert some control, there were many injuries. In addition to challenge matches, members of the troop would engage each other in “combat,” and among the most popular would be a woman with a wooden naginata against a man armed with a wooden or bamboo replica of a sword.

A match at the dojo of Chiba Shusaku between naginata and shinai (late 1800s)

One of the most remarkable of these women was Murakami Hideo, who became a seventeenth-generation headmistress of Toda-ha Buko-ryu. The little that we know of her life-story cries for a novel in her name. She was born in Shikoku in 1863 and as a young girl studied Shizuga-ryu naginatajutsu. When her teacher died, she moved to another area to study Ippon Sai Ichiden-ryu. Still in her teens, she left her home and went to Kyushu, wandering from dojo to dojo. At one point, she studied a form of Shinkage-ryu. Then she continued her travels in Honshu, traveling alone, testing her skill against other fighters, studying as she went. Imagine a tiny, young woman, little more than a girl, marching through the Japanese countryside, alone, without employment, walking from one dojo to another. This was a time when women were severely restrained in their choice of lifestyle and employment, but Murakami went her own way, inviolate.

She reached Tokyo while in her early twenties and became a student of Komatsuzaki Kotoo, and possibly Yazawa Isao, the fifteenth- and sixteenth-generation teachers of Toda-ha Buko-ryu. By now, Murakami was very strong, and she was awarded the highest license (menkyo kaiden) in the school while still in her twenties. She opened a dojo in the Kanda area of Tokyo called the Shusuikan (Hall of the Autumn Water).

Murakami was unable to read or write, so she was not able to make a living. At some time, then, she joined the gekken kogyo. Fighting with a chain-and-sickle or naginata, she took all challenges from the audiences. There are no reports of her ever losing. In her later years, she was able to make ends meet as a teacher, but she was always poor. According to those who knew her in her old age, she was a tiny, kind, but wary women, always ready to invite you to supper. She could drink anyone under the table. As far as is known, she lived alone and she died alone.

Murakami Hideo of Toda-ha Buko-ryu with her successor, Kobayashi Seiko

As these matches were for the entertainment of a paying audience, they soon degenerated to what must be considered the pro-wrestling or “Ultimate Fighting Championship” of the Meiji period with waitresses serving drinks in abbreviated kimono and drunken patrons cheering in the stands. Matches became dramatic exhibitions, vulgar parodies of the austere warrior culture from which they had emerged. Discouraged by the police who regarded them as a threat to public order, the gekken kogyo disbanded within a few years. Nonetheless, they can be regarded as the first precursors of modern martial sport in Japan–competition for the sake of comparing skills and entertaining an audience.

Murakami Hideo and Kobayashi Seiko of Toda-ha Buko-ryu, teaching at a young girl’s academy

Women’s Martial Training in Modern Times

As martial arts continued to be integrated into public education during the first decades of the Showa period (1926 to 1990 c.e.), the practice of naginata came to a crossroads. Judo, kendo, and, later, karate were made to be practiced in a standardized form. Naginata training, however, was still confined to the adaptation of specific ryu to physical education classes.

When taught to groups of young people, however, even the most traditional ryu must change. I have seen pre-Second World War photographs of a variety of koryu taught en masse, with lines of children diligently swinging weapons in unison. Other pictures show young children phlegmatically plodding their way through kata. Form practice means something very different to warriors trying to get an edge in upcoming battles than it does to young teenagers attending gym class at the local high school. Therefore, competitive practice became more and more popular not only as a means of training, but also as a way of holding the interest of young people who, understandably, could not see the value of kata practice alone. In competition, a light wooden naginata covered with leather was first used; later, for safety, bamboo strips were attached to the end of a wooden shaft in imitation of kendo shinai. This replica weapon is light and whippy, allowing movements impossible with a real naginata. As rules developed and point targets were agreed upon, the techniques useful for victory in competition began to differ from those used by the old schools, each of which had been developed for different terrain and varied combative situations. Naginata practice began to develop into something new–a competitive sport.

Not all teachers were opposed to this universalistic trend, given its congruence with the strong centralization of state power at this time. During the Second World War, some naginata teachers, notably Sakakida Yaeko, in conjunction with the Ministry of Education created the Mombusho Seitei Kata (Standard Forms of the Ministry of Education). Sakakida had been, and remains, a practitioner of Tendo-ryu and was an avid competitor in naginata matches against kendo students. She states that she found that the different styles of the old ryu were not suitable to teach to large groups of schoolgirls on an intermittent basis. Given the conditions in which she had to teach, she felt, also, that it was too difficult for the girls to learn the sword side of the kata, so she began to emphasize solo practice with the naginata. Finally, she was concerned that they might study one ryu in primary school and another in secondary school, thus being required to relearn everything each time they switched schools.

As a result of these difficulties, she and several associates created totally new kata that focused upon the naginata against naginata. This combination is not unknown among koryu, but it is rather uncommon. Notable ryu that focus upon dual naginata practice include Toda-ha Buko-ryu, Higo Ko-ryu and Seiwa-ryu. Naginata instructors of traditions which emphasized the naginata against the sword could not, however, be forced to abandon their schools to enter one of the few, often obscure traditions that did have dual naginata forms. No one could imagine that teachers who had invested years, even decades, of training in one tradition would join another that was suddenly appointed the standard bearer by the state. Most systems emphasizing more than one weapon were almost unteachable within the school environment. Yet the needs of society and the state that dictated those needs seemed to require an efficient, simple method of teaching youth en masse. The Mombusho forms, made for the express purpose of training school children, were the result. The Mombusho adopted these kata in 1943.

Something however, seems to have been lost in the process. Geared for children rather than warriors, these forms are, as a result, simplistic and somewhat lacking in character. The singularity that made the old ryu strong was sacrificed in favor of a generic mean. Teachers and students of the classical ryu received scant instruction in these new forms and were assigned “territories” made up of several grammar schools. As part of their preparation, the teachers were instructed in how to give “pep talks” to the girls. These talks included warnings about the barbarism of invading armies and the need for girls to protect themselves and their families. But the protection was not intended for the integrity of the girls themselves, but as “mirrors of the Emperor’s virtue.”5

Nitta Suzuyo, nineteenth-generation lineal successor to Toda-ha Buko-ryu recalls teaching these forms to girls from twelve to seventeen years old. Still a young woman herself, she was dispatched to instruct as her teacher, Kobayashi Seiko preferred to continue to teach her traditional ryu in private. As part of the training for teachers, Nitta was told that the most important thing was to boost the girls’ morale and strengthen their spirit in case of an enemy landing. She said that the girls liked the training, which was done in place of “enemy sports” such as baseball or volleyball.

Women were said to personify the spirit of bushido because their “nature” was to be selfless and nurturing. They were believed to be the basis of society because of their place in the education of children. It was claimed that martial arts training would develop the attention to details needed for housekeeping, food preparation, caring for the sick, and making a “friendly atmosphere.” A woman trained in naginata was supposed to be soft but strong, willing to be selfless but decisive, and above all, patient and enduring. The strong body she developed from training was necessary to keep healthy and active to carry out all her work. She was said to have a “full spirit” and strong beauty. One teacher’s manual, written in the middle of Japan’s war years, states, “the study of naginata, home economics, and sewing would develop the perfect woman.”6

In 1945, the war finally ended. The occupation forces were fearful of anything that seemed to be connected to Japan’s warlike spirit and they banned martial studies. Thousands of swords were piled on runways, run over with steamrollers, and then buried under concrete construction projects. Donn Draeger recounted to me the sight of those swords, flashing in the sun in shards of gold and silver, crackling and ringing under the roar and stink of the steamrollers.

After a eight years, however, these bans were lifted and the first All Japan Kendo Renmei (Federation) Tournament was held in 1953. At a meeting held afterwards, Sakakida and several of the leading naginata instructors of Tendo-ryu and Jikishin Kage-ryu made plans for the institution of a similar All Japan Naginata-do Renmei. It was decided to adopt the Mombusho kata as the standard form of the federation, with only a few minor changes. They also decided to eliminate the writing of naginata in characters (long blade) and (mowing blade) and, to indicate their break with the past, spell it in the syllabary whose letters have only sound values. This martial sport has come to be called atarashii naginata (new naginata).

The change of characters in writing “naginata” may seem to be a trivial one, but it is not. The philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty refers to language as “sublimated flesh.” By this, he means that language is the concentrated essence of human existence and determines how life will be lived. This change in how “naginata” is written states decisively that atarashi naginata is no longer a martial art, using a weapon either to train combat skills, or to demand, through its paradoxical claim as a “tool for enlightenment,” a focused and integrated spirit. Instead, they have created a sports form, martial in both appearance and “sound,” but not in “character.”

Atarashii naginata forms competition

Atarashii naginata is composed of two parts: kata and shiai. According to some of its leading instructors, particularly those of this generation, the kata were created by taking “the best techniques from many naginata ryu.” Perhaps some may feel that I am stating this a little too strongly, but this is an absurd idea. The forms of the various ryu are not mere catalogues of separate techniques to be selected like bon-bons in a corner candy store. They are interrelated wholes, permeated with a sophisticated cultivation of movement, for combative effectiveness and/or spiritual training. Sakakida herself only states that she observed the old ryu and tried to absorb their essence. Then, forgetting their movements entirely, she devised the new kata.

These first-level kata, derived from the Mombusho forms and now called shikake-oji, are a set of simple movements requiring straight posture and sliding footwork. Practice is done with an extremely light shinai or wooden naginata.

These forms are used in kata contests. Two pairs of contestants perform the same kata, and they are judged on the “correctness” of their movements. There is a second level of forms, called the Zen Nihon Naginata Kata, which is only taught after a student reaches third dan level. Some claim that they are the product of a study of the naginata kata from fifteen different martial traditions. A committee of members of the Naginata Renmei allegedly derived what they considered to be the essential movements of these ryu and combined them into a linked set of seven kata. However, according to martial arts scholar, Meik Skoss, the forms are, in fact, largely made up of techniques from Tendo-ryu and Jikishin Kage-ryu.

Not all of the old teachers are enamored of atarashi naginata. Abe Toyoko, a senior instructor of Tendo-ryu, in a marvelous interview in “Fighting Woman News” discussed these forms with Kini Collins in the early 1980s. Abe Sensei was one of the strongest of all the strong women in Tendo-ryu and had always been rather a lone wolf. Japanese social groups can be rather wearing, and Abe Sensei was well known for her blunt speech and strong opinions. Her almost gruff power was reflected in her art and her words. The first time I saw her in a group of other Tendo-ryu instructors, she stood out like a mother bear. She never seemed to try to look pretty or graceful–simply effective.

Tendo-ryu Nito (two-sword) technique

This new stuff. One, up with the stick. Two, down with it. Three, put it away. Well, that is one way of teaching, but there is something else, I only know it as kokoro (heart, spirit). Pull it in on one, out on two, lift on three, well, you try it! If you do it only with an awareness of moving and no concept of kokoro, you are so wide open it isn’t even funny. This is what I want to teach. How to react when your partner doesn’t respond in the way you are used to. This is what it hasn’t got, the new naginata. There is no thought outside the form, there isn’t even any path for this kind of thinking.

When they got started about twenty years ago, they wanted to get going fast, so it was forced: trying to bring everyone into the same line, changing everyone’s style to fit a new form. Taking from the right, from the left, trying to get everyone to agree. Just to get started, never mind the outcome. But all these schools and the techniques themselves are separate entities governed by separate principles of movement and thought. This new thing has absolutely none of these principles.

Teaching the form of a technique rather than the substance and form leads to nothing. Worse than nothing. Some teachers say that form is enough for women. No way! That really makes me angry. Who needs form? In Japanese, there is a word, rashikute (to seem or to be like something), like a woman, like a man, like a …I don’t know what, but it really colors our language. It has meaning though, not just the surface stereotypes. A woman’s whole life is being womanlike. To be like a woman is not simply to be soft. To be womanlike is to be as strong or as soft, as servile or as demanding as a situation calls for. Be appropriate and act with integrity. This isn’t being taught at all. And it is the heart of budo, it is alive in the practice of it. 7

The atarashii naginata competitions are an imitation of those of kendo. Sadly, the matches often resemble a game of tag with the shinai. It is striking to see how few of the kata movements are utilized by the practitioners. The kata movements, thus, are not relevant to the other wing of the system.

Abe Toyoko of Tendo-ryu explaining how to lock an opponent’s elbow, immobilizing her so that she cannot escape as she is stabbed with a short weapon

The contestants are well armored, but there are only eight designated targets: the top of the wrists, the top and sides of the head, the throat, the sides of the trunk, and the shins. Winning points are decided by referees. Considering that the bamboo end of the shinai is supposed to represent the blade of the naginata, the contests are often a little confusing for outsiders. Many potentially lethal or incapacitating strikes go unheeded because they do not represent a “point.” In addition, the ishi-zuki (butt) of the shinai is rarely used in such competitions, although it was an essential component of the use of the weapon in real combat. Because one scores by striking target areas with an extremely light replica of a weapon, the emphasis is on speed. The contestants hold their bodies upright on the balls of their feet to slide and jump in and out quickly, footwork suited only to the polished floors of gymnasiums and dojo. Because there is no sense of danger or even a need to protect undesignated targets, many competitors do not move or respond in a natural way. Blows that would sever arms, disfigure, or even kill are ignored because they are not designated targets. Again, consider the words of Abe Toyoko:

Modern naginata competition

Modern naginata competition

Modern naginata competition

Our matches didn’t have all that quick jumping and dancing. They never did. There has to be a lot of aware-ness before and during a match. You can’t just enter one casually. Naginata were weapons with blades that cut, and we have to keep that respect even with the bamboo blades we use today. The first tournament I saw my teacher in, it was amazing. She walked her opponent all the way across the hall, from the east side to the west side, not using any technique, just her stance and spirit. Everyone, even the old teachers were enthralled. Then she moved to cut, just once. And I was hooked. She found my timing and caught me. She won the match too.

Abe Toyoko. Photo courtesy of Kini Collins

By removing the considerations of one’s own death and one’s responsibility for the other’s fate, atarashi naginata may have removed the major impetus for the development of an ethical stance. All that may remain for many trainees is a sport with the emphasis on winning or losing a match.

Many naginata-ryu teachers have entered the modern association and have attempted to teach both their old traditions and atarashi naginata. However, only a few of their students are willing to practice the old ryu. These martial traditions, with footwork suited to rough terrain and low postures suited to exerting leverage in cutting and protecting all of the body, seem to be awkward and old fashioned to atarashi nagi-nata students who focus on modern competition. This has resulted in the abandonment and demise of most of the old martial traditions within the last fifty years. Often the only reason young people practice the old school at all is “just so it won’t be forgotten.”

When searching out old schools, it was disheartening to see how many schools who had made common cause with atarashi naginata, rather than getting new students, ended up with none. In the early 1980s, it took three months of concentrated effort to locate Sakurada Tomi, the eighteenth-generation headmistress of the Suzuka-ryu, one of the foremost naginata instructors in Japan, the last headmistress of her tradition. Numerous calls to both the local and national offices of the Atarashi Naginata Association were met with indifference, although she had been perhaps the most significant figure among women martial artists in Sendai city. We finally located her, alone, without students or family.

The magnificent Sakurada Tomi, eighteenth-generation headmistress of the Suzuka-ryu

With the “official line” trivializing the classical schools to young impressionable students, the older ryu, with the exception of Tendo-ryu and Jikishin Kage-ryu, are largely ignored, except to be invited to give demonstrations at the intermissions of atarashi naginata competitions. Among the traditions that have almost or completely died out in the last twenty years, we must number Choku Gen-ryu, with its massive nine-foot-long naginata, the vital and powerful Suzuka-ryu and elegant Anazawa-ryu. The dynamic Muhen-ryu, another school that interestingly uses naginata and bo (long-staff) interchangeably within the same forms, is also largely ignored by the atarashi naginata students who study under its headmistress.

It must be faced, however, that much of the demise of the old traditions is the responsibility of practitioners themselves who either could not find a way to make their art relevant to the younger generation, or have no idea themselves of the value of the tradition passed on to them. Illustrative of the latter was one woman, an atarashi naginata competitor and teacher who had practiced a bujutsu ryu since childhood.

I said to her, “Your training in classical naginata must give you a real advantage in strength over the other participants in contests.” In response she complained, “No matter what I do, the naginata-jutsu techniques creep into my atarashi naginata movements and ruin it. We are all supposed to do it the same way, but I just can’t!”

This attitude, too, is countered by Abe Toyoko:

I see lots of people today, jumping from one new thing to another, not getting settled. I really think people need something in the foundation, some deeply rooted place in their lives. I see this even in the judging of naginata matches. It used to be so different, this judging. There were only two judges per match, and they were deliberate and subtle, not jumpy and conforming like the ones today. Even their movements had more meaning. The judges used to have individual styles, their own way of signaling points. Now everyone has to do it the same way. You won’t believe this. They stopped a match once, one I was judging, and asked over the loudspeaker if I would raise my arm a few more degrees when signaling. Do you believe it? And just a couple of years ago, I was judging with another teacher. One of the competitors moved, just moved a little, and the other judge signaled a point. I asked the two women in the match if a point had been made, and they both said no. But because the judge had ruled for it, it was declared valid! I haven’t judged since. I don’t want to be a part of teaching people how to win cheaply or lose unfairly.

Conclusion

From an essay in history sprinkled with only minor leavenings of personal opinion, I find it necessary to end on a truly personal note. Approximately twenty years ago, I began a project on the use and history of the naginata. The initial stages of this were done in the company of Ms. Kini Collins: I later took the project over by myself, and a series of essays, many of which are in this book, are the result.

This weapon attracted me the first time I saw it, not as a “woman’s weapon,” but one suited for me, a man of six and a half feet and over 220 pounds. Araki-ryu, the first martial tradition I entered, uses both the nagamaki and a large naginata in a dramatic, almost wild fashion probably very similar to the methods of strapping foot soldiers and warrior monks in earlier periods of Japanese history.

I later entered Toda-ha Buko-ryu, and, thereafter, was able to study a system that has been led by women for over one hundred and fifty years. Toda-ha Buko-ryu is still very much an art of war, but it is a martial tradition that developed and permutated in the Edo period. It is a paradoxical art–every movement is an attack. There is no stance with the weight on the back foot, and no purely defensive techniques. Yet in its elegant, graceful movements, it shows some of the sophistication that develops in a martial art when warriors have the leisure afforded them by peace to study movement and refine it in depth. It is also imbued, for lack of a better term, with a profound feminine sensibility.

Three trainees of modern-day Toda-ha Buko-ryu

I became deeply influenced by both of these martial traditions, both in themselves and as embodied in the person of their instructors. Of most relevance to this piece is Nitta Suzuyo Sensei of Toda-ha Buko-ryu, a refined, gracious woman, unfailingly courteous and remarkably strong in every sense that really matters. The feminine leadership within this school has been a gift and a challenge to me. I have been required to model myself, in some respects, on a tiny, five-foot-tall, aristocratic Japanese woman, to learn the essence of what she offers without either slavish imitation or an arrogant assumption on my part that I can simply adapt her art to my large, Western frame. She has been a model to me in my own profession dealing with the diffusion and de-escalation of violence. It was from her that I learned the power of tact, how courtesy alone can often resolve what force of arms may not.

Nitta Suzuyo, nineteenth-generation headmistress of Toda-ha Buko-ryu

I have, therefore, an intense attachment and respect for the traditional koryu and firmly believe that the best of my own life’s work could never have occurred without my study in them. It is fair to say that there have been instances in which I have been able to save people’s lives using knowledge that I could have acquired in no other fashion than by training in archaic Japanese martial arts, and in none of these instances was I forced to engage in anything like hand-to-hand combat.

I believe that competitive martial sports can be wonderful activities as well. My own rather limited years of experience in judo and Muay Thai and ongoing cross-training in modern grappling systems have certainly brought that home to me. Competition can impart a sense of trust in one’s ability as well as expose one’s weaknesses. Such study can create a more self-aware individual, a person far more valuable to a community than one would imagine a mere sportswoman or sportsman to be. Thus, martial sports are not mere sports.

Atarashii naginata is a significant part of the lives of probably several million women. Something of such consequence cannot simply be shoved aside in a disdainful conservative critique that it is degenerated, watered-down martial arts. Like any other activity, martial training must continue to grow and develop if it is to remain appropriate to the times in which it exists.

However, in the rush to create martial sports that are open to anyone and useful to everyone, much of profound value is irrevocably lost. Tradition, far from being a mere nostalgia for the past, can be a powerful force to unite a people. Traditions can make people aware of their origins and singularity. Even though ryu were created hundreds of years ago to deal with problems specific to those times, there is no reason to relegate them to preservation societies or museums, mere curiosities to be trotted out several times a year as intermission entertainment during competitive matches. Since the ryu were developed for specific regions, offering specific psychological and combative methods, they can still be living traditions, strong and direct connections with the past. They were, and can be, powerful forces imparting loyalty, morality, and courage, as well as a sense of togetherness. That which helped create viable communities in the Muromachi era is still relevant today. Practiced with the intention of strengthening its community, study of any ryu can develop a cohesive courage and depth of feeling in its members. This could help maintain a community as a living entity, one not as vulnerable to exploitation or incorporation into a superficial mass culture.

Finally, the knowledge contained in the ryu was bought in blood. I do not idealize the act of killing on a battlefield. I do idolize those who passed through such experiences and, rather than leaving mere reminiscences of brutal acts committed or suffered, attempted to pass on a treasure distilled from the horrors of war: the knowledge of how to survive; a method of continuing the bonding that occurs on the battlefield well after the battle was fought, maintaining those ties of trust once the shackles of fear and rage are no longer needed to force people together; and perhaps most important, a tradition for handing on the depths of ethical and spiritual teachings contained in the heart of systems created ostensibly only for war. On my own father’s gravestone are the words of Rabbi Hillel, “In a land where there are no men, strive thou to be a man.” This is the morality learned on the battlefield, however the battlefield might be defined. This is an ethic won only through facing the potential for death: one’s own at the hands of others and others’ death at our own hands. To strive towards this ethical sense is what has led me through my over thirty years of martial training, and this is, to me, the essence of what is contained in the heart of many of the traditional ryu. For the men and women in most modern martial sports, and, specifically, for the (mostly) women who train in modern sports naginata, I believe that despite all the fine things they may have gained in the abandonment of traditional martial practice, they may have lost even more wondrous things. To wish that history were different is ultimately foolish. But foolish as it may be, I wish that they could have both.

Bibliography – Women Warriors of Japan

English Language Sources

- Amdur, Ellis, “The Development and History of the Naginata,” in Journal of Asian Martial Arts, Vol. 4, no. 1, 1995, pp., 32-49.

- Amdur, Ellis, “Divine Transmission Katori Shinto Ryu,” in Journal of Asian Martial Arts,Vol. 3, no. 2, 1994, pp. 48-61.

- Amdur, Ellis, “The Higo Ko Ryu,” in Furyu, Vol. 1, no. 3,1994/95, pp., 49-54.

- Amdur, Ellis, “The Rise of the Curved Blade,” in Furyu, Vol. 1, no. 4,1995, pp., 58-68.

- Dore, R.P., Education in Tokugawa Japan, Routlege and Kegan Paul, London, 1965.

- Draeger, Donn, and Robert Smith, Asian Fighting Arts, Kodansha, Ltd., Tokyo, Palo Alto,1969.

- Frederic, Louis, Daily Life at the Time of the Samurai 1185-1603, trans. from French by Eileen Lowe, Tuttle Books, Rutland and Tokyo, 1973.

- Mason, Penelope E., A Reconstruction of the Hogen-Heiji Monogatari Emaki, Garland Pub., Inc., New York and London, 1977.

- McCullough, Helen Craig, trans. with an introduction, Yoshitsune, University of Tokyo Press, Tokyo, 1966.

- McCullough, Helen Craig, trans. with an introduction, Taiheiki, Charles E. Tuttle Co., Rutland and Tokyo, 1979.

- Sadler, A. L., trans. Heike Monogatari, Kimiwada Shoten, Tokyo, 1941.

- Varley, Paul, Warriors of Japan as Portrayed in the War Tales,University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, HI, 1994.

- Wilson, William R., trans. with an essay Hogen Monogatari, Sophia University Press, Tokyo, 1971.

Japanese Language Sources

- Mitamura, Kunihiko, Dai Nippon Naginata Do Kyoden, Shubundo Shoten, Tokyo, 1939 — prewar school instructor’s book for Tendo Ryu.

- Kendo Nippon Monthly, 1982 No. 7 “Naginata; Interview with Sakakida Yaeko.”

- Sonobe, Shigehachi, Kokumin Gakko Naginata Seigi, Toytosho Pub., Tokyo, 1941 — prewar school instructor’s book for Jikishin Kage Ryu.

- Takenouchi Ryu Hensan I-in Kai, Takenouchi Ryu, Nochibo-Shuppan Sha, Tokyo, 1979 — large book detailing the history and techniques of the Takenouchi Ryu.

- Yazawa Isako, Naginata no Hanashi,1916 — in a collection of martial arts articles held by the Toda ha Buko Ryu.

Copyright ©2002 Ellis Amdur. All rights reserved.